How we sped up an ASP.NET Core endpoint from 20+ seconds down to 4 seconds

11 Jul 2020This post has initially been published on the Telstra Purple blog at https://purple.telstra.com/blog/how-we-sped-up-an-aspnet-core-endpoint-from-20-seconds-down-to-4-seconds.

Introduction

We have an internal application at work that sends large payloads to the browser, approximately 25MB.

We know it is a problem and it is on our radar to do something about it. In this article, we’ll go through the investigation we performed, and how we ultimately brought the response time of this specific endpoint from 20+ seconds down to 4 seconds.

The problem we faced

We run this application on an Azure App Service, and the offending endpoint had always been slow, and I personally assumed that it was due to the amount of data it was returning, until one day for testing purposes, I ran the app locally and noticed that it was much faster, between 6 and 7 seconds.

To make sure we were not comparing apples to oranges, we made sure that the conditions were as similar as they can be:

- We were running the same version of the app — that is, the same Git commit, we didn’t go as far as running the exact same binaries;

- The apps were connecting to the same Azure SQL databases; and

- They were also using the same instance of Azure Cache for Redis.

The one big difference that we could see was that our dev laptops are much more powerful in regards to the CPU, the amount of RAM or the speed of the storage.

The investigation

What could explain that this endpoint took roughly 3 times less to execute when it was connecting to the same resources?

To be perfectly honest, I can’t remember exactly what pointed me in this direction, but at some point I realised two things:

- Starting with ASP.NET Core 3.0, synchronous I/O is disabled by default, meaning an exception will be thrown, if you try to read the request body or write to the response body in a synchronous, blocking way; see the official docs for more details on that; and

- Newtonsoft.Json, also known as JSON.NET, is synchronous. The app used it as the new System.Text.Json stack didn’t exist when it was migrated from ASP.NET Classic to ASP.NET Core.

How then did the framework manage to use a synchronous formatter while the default behaviour is to disable synchronous I/O, all without throwing exceptions?

I love reading code, it was then a great excuse for me to go and have a look at the implementation.

Following the function calls from AddNewtonsoftJson, we end up in the NewtonsoftJsonMvcOptionsSetup where we can see how we replace the System.Text.Json-based formatter for the one based on Newtonsoft.Json.

That specific formatter reveals it’s performing some Stream gymnastics — see the code on GitHub.

Instead of writing directly to the response body, the JSON.NET serializer writes (synchronously) to an intermediate FileBufferingWriteStream one, which is then used to write (asynchronously this time) to the response body.

The XML docs of FileBufferingWriteStream explain it perfectly:

A Stream that buffers content to be written to disk. Use

DrainBufferAsync(Stream, CancellationToken)to write buffered content to a target Stream.

That Stream implementation will hold the data in memory while it’s smaller than 32kB; any larger than that and it stores it in a temporary file.

If my investigation was correct, the response body would’ve been written in blocks of 16kB. A quick math operation would show: 25MB written in 16kB blocks = 1,600 operations, 1,598 of which involve the file system. Eek!

This could explain why the endpoint was executing so much quicker on my dev laptop than on the live App Service; while my laptop has an SSD with near-immediate access times and super quick read/write operations, our current App Service Plan still runs with spinning disks!

How can we verify whether our hypothesis is correct?

Solution #1, quick and dirty

The easiest way I could think of to get the file system out of the equation was to enable synchronous I/O.

// Startup.cs

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services

.AddControllers(options =>

{

// Suppress buffering through the file system

options.SuppressOutputFormatterBuffering = true;

})

.AddNewtonsoftJson();

}

// Controller.cs

public Task<IActionResult> Action()

{

// From https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/core/compatibility/aspnetcore#http-synchronous-io-disabled-in-all-servers

// Allow synchronous I/O on a per-endpoint basis

var syncIOFeature = HttpContext.Features.Get<IHttpBodyControlFeature>();

if (syncIOFeature != null)

{

syncIOFeature.AllowSynchronousIO = true;

}

// Rest of the implementation, ommited for brevity

}

Making both of those changes is required because:

- Only suppressing output buffering would throw an exception, since we’d be synchronously writing to the response body, while it’s disabled by default;

- Only allow synchronous I/O wouldn’t change anything, as output buffering is enabled by default, so that updating projects to ASP.NET Core 3.0 doesn’t break when using Newtonsoft.Json and sending responses larger than 32kB.

Locally, I observed a response time of ~4 seconds, which was a substantial improvement of ~30%.

While it was a good sign that our hypothesis was correct, we didn’t want to ship this version. Our application doesn’t get that much traffic, but synchronous I/O should be avoided if possible, as it is a blocking operation that can lead to thread starvation.

Solution #2, more involved, and more sustainable

The second option was to remove the dependency on Newtonsoft.Json, and use the new System.Text.Json serialiser. The latter is async friendly, meaning it can write directly to the response stream, without an intermediary buffer.

It wasn’t as easy as swapping serialisers, as at the time of writing System.Text.Json it was not at feature parity with Newtonsoft.Json. My opinion is that it’s totally understandable as JSON.NET has been available far longer.

Microsoft provides a good and honest comparison between the two frameworks: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/standard/serialization/system-text-json-migrate-from-newtonsoft-how-to

The main thing for us was that System.Text.Json doesn’t support ignoring properties with default values. For example: like 0 for integers.

We couldn’t just ignore this, because the payload is already so large, adding unnecessary properties to it would have made it even larger.

Luckily, the workaround was relatively straightforward and well documented: we needed to write a custom converter, which gave us total control over which properties were serialised.

It was boring, plumbing code to write, but it was easy.

In the end, we removed the changes mentioned above, and plugged in System.Text.Json.

// Startup.cs

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services

.AddControllers()

.AddJsonOptions(options =>

{

// Converters for types we own

options.JsonSerializerOptions.Converters.Add(new FirstCustomConverter());

options.JsonSerializerOptions.Converters.Add(new SecondCustomConverter());

// Make sure that enums are serialised as strings by default

options.JsonSerializerOptions.Converters.Add(new JsonStringEnumConverter());

// Ignore `null` values by default to reduce the payload size

options.JsonSerializerOptions.IgnoreNullValues = true;

});

}

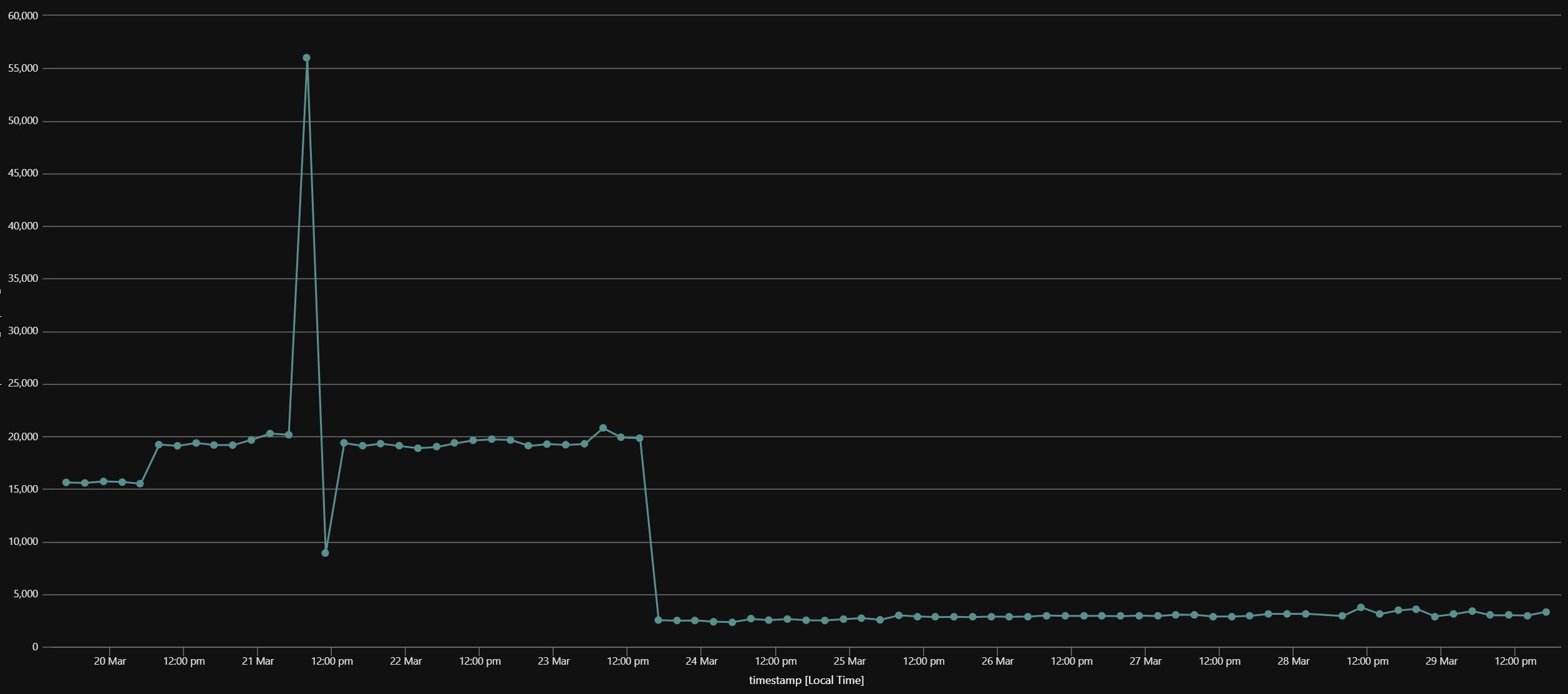

We gave it another go, and again achieved a consistent 4-second response time on that endpoint 🎉. After deploying this new version to our App Service, we were stoked to see a similar response time there as well.

Conclusion

This was a super fun investigation, and I was once again super happy to dig into the ASP.NET Core internals and learn a bit more about how some of it works.

While I realise our case was extreme given the size of the response payload, in the future I’ll think twice when I encounter a code base using Newtonsoft.Json, and see how hard it’d be to move to System.Text.Json. There’s definitely a big gap between both, but the team is hard at work to fill some of it for .NET 5.

See the .NET 5 preview 4 announcement and search for the “Improving migration from Newtonsoft.Json to System.Text.Json” header to learn more about where the effort goes.

You can also check issues with the “area-System.Text.Json” on the dotnet/runtime repository, or take a look at the specific project board for System.Text.Json if you want to be even closer from what’s happening.